What’s the most common topic in the change management literature? “Overcoming resistance to change.” What’s the focus that statement implies? In the stress of leading change, despite our best intentions, it can feel like we’re doing something “to” others, or “against” others, or even “in spite of” others – instead of with and for our partners in change. As I’ve written about before, what can we control? Only ourselves – our mindsets and our behaviors. It’s amazing how often when we change, others change as well.

I learned this lesson early in my career when I was helping start-up the “people-side” of a US-Japanese joint venture and USW-represented steel mill, founded upon a very unique, team-base culture. We each have our own style of leading change, and mine is that of a Champion, characterized by engaging people to work together toward an aspirational goal. I forged powerful partnerships from the joint union-management US/Japanese leadership team to the operators and maintenance technicians on the front lines, who were all passionate to build a steel mill that ran very differently than those in the past.

However, I realized early on that I was not getting traction with the manager of a key engineering group. He “resisted” freeing his engineers up to participate in design team meetings. In a team-based manufacturing facility, deep and daily involvement between engineering, operations and maintenance is a pivotal success factor to achieve the vision, and we needed engineering’s input and buy-in to the communication mechanisms and decision-making boundaries we were designing.

In the engineering manager’s words, “our president has said that we have four priorities for the start-up – safety, quality, production, and teams. Teams are number four, so I’m focusing my engineers on numbers one to three.” He came from the US parent company’s largest steel making facility, which was very autocratically managed, and that’s how he thought a steel mill should be run – top-down, not participatively. Initially, I categorized him as a “resister,” and I attempted to “overcome” his resistance in a variety of ways, none of which worked.

Eventually I got a bit “smarter”, and had an insight that was one of the first steps to building my own Change Intelligence. I looked in the mirror and reflected upon what I was doing, or not doing, or overdoing that might be causing resistance in him. What I realized was that his “top three priorities” were legitimate. Start-ups are chaotic, and there were a great many demands on his engineers’ time. In many ways, he was accurately assessing the risks of a team-based culture, including ones that perhaps I had not taken fully into account.

I scheduled a meeting with the engineering manager, and apologized. I told him I wanted to hear his concerns and understand his objectives. Based on this new information, I asked if we could explore ways to build a detailed project plan that would integrate his accountabilities into our design team’s work stream. He agreed, and we did so. While he never became a fan of the team approach, he followed-through with our plan. Today, almost 30 years later, a young engineer he assigned to our design team is now the president of the mill and the unique work culture is still thriving.

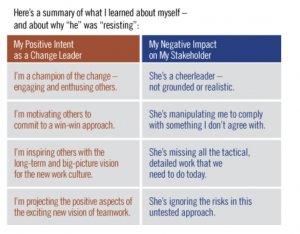

My optimism was perceived by him as Pollyannaish, and his realism was perceived by me as pessimism. My enthusiastic style was perceived by him as superficial glibness, and his reserved style was perceived by me as detached resistance. By changing the only thing I could control – my mindset and my behaviors – recognized that what looked like resistance in the engineering manager was in fact a blind spot in my own ability to create an effective partnership in jointly leading change. By changing myself first – or rather, by adapting my style – I did not change the engineering (which of course was not my goal!) but I was able to influence him (and him, me) toward a mutual solution.

My optimism was perceived by him as Pollyannaish, and his realism was perceived by me as pessimism. My enthusiastic style was perceived by him as superficial glibness, and his reserved style was perceived by me as detached resistance. By changing the only thing I could control – my mindset and my behaviors – recognized that what looked like resistance in the engineering manager was in fact a blind spot in my own ability to create an effective partnership in jointly leading change. By changing myself first – or rather, by adapting my style – I did not change the engineering (which of course was not my goal!) but I was able to influence him (and him, me) toward a mutual solution.

That’s Change Intelligence in a nutshell: the awareness of our style of leading change, and the ability to adapt our style to be optimally effective across people and situations. If you’re encountering what looks like resistance in a key stakeholder, I invite you to likewise turn the mirror back on yourself and reflect on these three questions:

- How might I be overdoing my strengths (in my example, I was over-selling the positives of the change)?

- How might I be missing or downplaying what is of vital importance to the change process (in my example, my optimism resulted in neglecting realistic concerns)?

- How might my positive intent unintentionally be creating a negative impact on others (in my example, I was perceived as talking at not with, and not seeking to understand before being understood)?